Uncategorized

June 2022

Hello Friends,

I invite you to join me on Sunday, June 12, 2022, from 2:00-4:00 pm for the opening of “Spheres and Sinospheres,” a solo exhibition curated by Sara Henry at the Voelker Orth Museum located at 149-19 38th Ave., Flushing (Queens), NY.

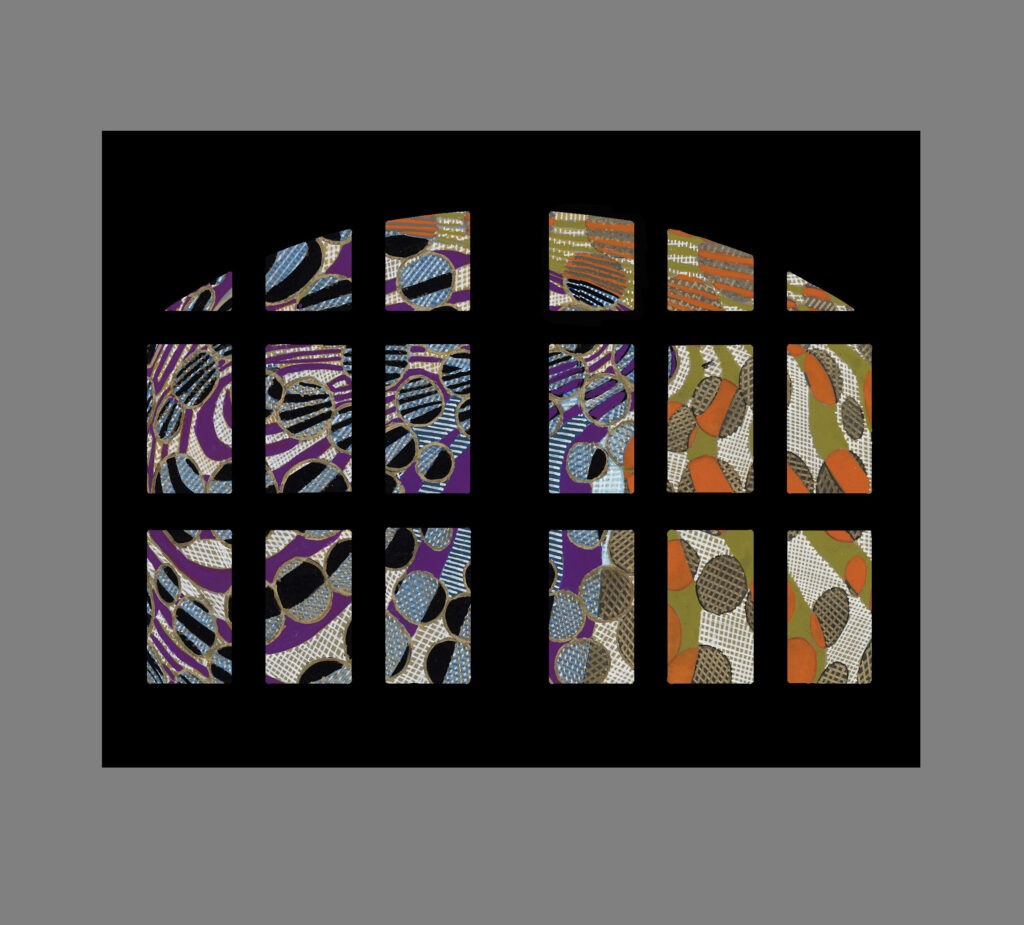

In the Middle of the Dream, limited edition archival print, 2011

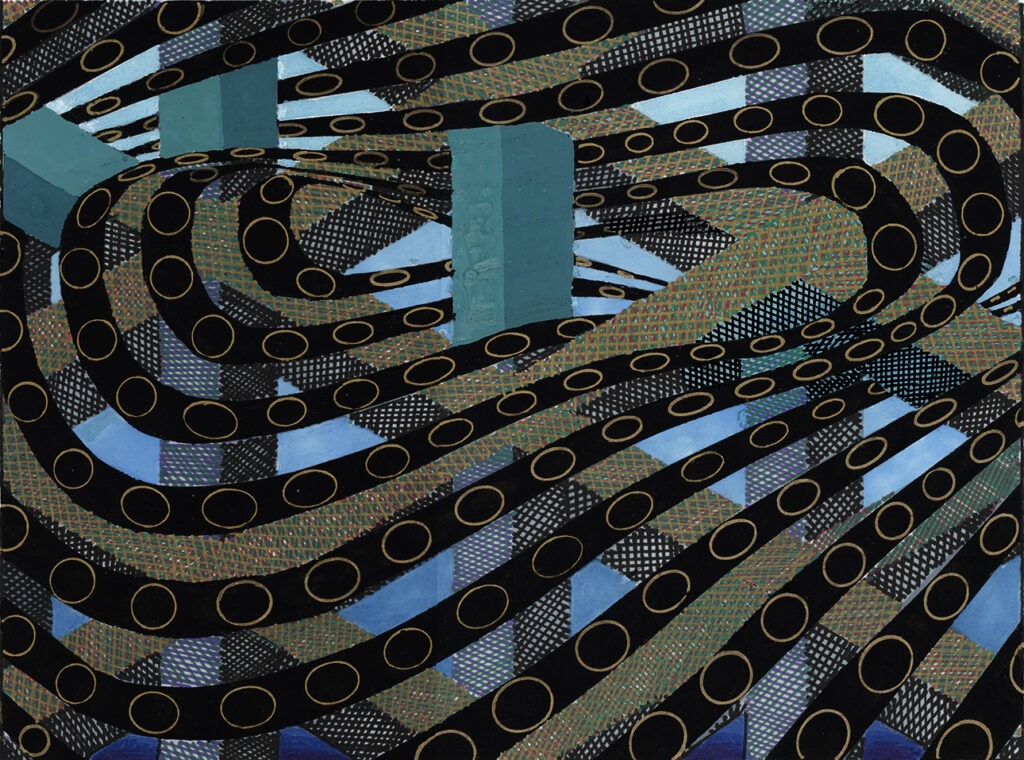

The show features examples from three different series of my work including Mandala paintings from the 2010’s, oil paintings on paper informed by Chinese Folk Art from the 2000’s, and a small gouache and oil marker on paper from my current geometric abstraction series.

Caravan, oil on paper, 22 x 30, 2007

The official name of the museum is The Volker Orth Museum, Bird Sanctuary and Victorian Garden. It occupies a two-story house that was constructed in 1891. The house was purchased in 1899 by a German immigrant named Conrad Voelcker, who moved in with his wife Elizabeth and infant daughter Theresa. After Voelcker’s death in 1930, the house became the home of his daughter, Theresa Voelker and her husband, Dr. Rudolph Orth. Their daughter, Elisabetha Orth, who lived in the house most of her life, established the organization which now runs the museum in her will. The property was designated a New York City Landmark in 2007.

This exhibition was the brainchild of Sara Henry, an Independent Curator and Art Writer, Professor Emerita of Art History and NEH Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Drew University.

Arabesque 4, oil on canvas, 30 x 30″, 2016

Nature Provides Mural featured in CODAmagazine: Art and Wellness

Nature Provides, mosaic, glass and brass sheeting, 8 x 18′, Patient Services Center, Western State Hospital, Lakewood, WA

Client: ArtsWA

Location: Lakewood, WA, United States

Completion date: 2020

Artwork budget: $69,000

Project Team

Fabricator: Steve Miotto, Miotto Mosaics

Project Manager: Chuck Zimmer, ArtsWA

Overview

Mosaic, glass, and brass sheeting mural, 8×18-ft, commissioned by Western State Hospital, Lakewood WA for a Patient Services Center in construction. I was selected by the Selection Jury, consisting of a selection of 8-10 women (plus the building architect) who would be working at the Center. The Center will house food preparation services and medical prescription services that serve the patient population. Western State Hospital is a historical hospital established to care for people diagnosed with psychological, emotional and/or mental problems, and it continues to be so.

Goals

I met with the Selection Jury and the building architect who told me they were looking for artwork that would refresh them in the course of their working days, perhaps energizing them since their work is demanding and fatiguing.

Process

The first time I met with the Selection Jury they directed me regarding the type of imagery they wanted to see. I went through a process of making designs following their instructions. We went back and forth many times until finally they said to the Project Manager that my proposals didn’t feel like the installed projects they had seen when they selected me to be the artist. Chuck Zimmer, the ArtsWA Project Manager finally explained to them that I was trying to follow their directives, but that what they originally liked about my work was its sense of energy and play, at which point they decided to give me free range to create what I wanted.

Additional Information

Freed of their instructions I was able to step away from a literal depiction of their ideas, and instead, design an abstract mural that metaphorically and sensually fulfilled what they were looking for.

Musings in the Midst of the Covid 19 Pandemic

IN THE MIDST OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

LIVING, READING, PAINTING IN NYC

Saturday, November 21, 2020

I read a book recently, The Inner Game of Tennis by W. Timothy Gallwey, that I wish I had read while I was still teaching. The book was published 30 years ago, is still in print, and has sold close to a million copies. It is only superficially about tennis.

Gallwey’s theory is that we are each made up of two people, one guided by the brain (the ego-driven self) that has internalized all the things we are told growing up, and the other, guided by the body (the inner self) that has its own inherent needs, its own demands and requirements. It is this inner self that should be guiding us through life, but socialization and education tend to fight against it. The inner self, Gallwey believes, is endowed with an instinct to fulfill its nature: it wants to enjoy, learn, understand, appreciate, express itself, rest, be healthy, survive, and be what it is in order to make its unique contribution in the world. This self comes with a constant gentle urging; the person who works in concert with his/her inner self will be attended by a certain type of contentment.

Gallwey writes that the first rule of successful living is recognizing that this inner self has all the gifts and capabilities with which we hope to accomplish anything, and it has its own requirements to live in balance with itself. To be able to listen to this self you have to let go of all good/bad judgments (of ourselves and others). Ultimately you want to be someone who is able to let go of anything — if necessary — and still be okay. Gallwey says we need to give priority to the demands of the inner-self in relation to all the external pressures from the ego-driven self.

Gallwey arrived at this philosophy through teaching tennis. He discovered that his students learned better if — instead of telling them what to do — he simply demonstrated actions, which allowed the students to by-pass, and not be distracted by his verbal instructions. This allowed the student’s body intelligence to kick in and emulate the demonstrated movements. Gallwey also says that there is no one right way to do anything in tennis; each person should be allowed to find his/her own way based on the uniqueness of their bodies.

I stumbled on this exact same notion teaching art which, like tennis, is a physical activity. I urged students stop thinking and simply allow themselves to try different things, a process that allowed their embodied intelligence to take over. I liked to refer students to the way they doodled, since doodling is an automatic, mindless activity guided by the hand, and relies on comfortable and natural gestures.

In 1974 when Gallwey wrote The Inner Game of Tennis, Zen Buddhism was not as prominent or as pervasive in American culture as it is today; reading Gallwey’s writing the philosophical parallels between his thinking and that of the American version of Zen Buddhism is inescapable. Both philosophies are founded on the belief that attachment to outcomes is what trips us up: as he said, “the aim is to be able to let go of anything — if necessary — and still be okay.” Gallwey extends the principles of his thinking to all activities, whereas when I was teaching, I thought these principles applied only to art making.

Gallwey and I both believe that, each person is actually born right and perfect for who he/she is, and that simply allowing ourselves to follow our innate sense, the one we come into the world with (placing this guidance ahead of what society and education tells us) we can realize our potential, and fulfill our destinies. To put it more succinctly, I believe what Miles Davis said, “The genius is the guy who is most himself.”

Wednesday, November 11, 2020

When I was in college a friend said she didn’t know what she wanted to do in life. I suggested she try figuring it out through a process of elimination by making a list of what she doesn’t want. She liked the idea but was troubled that she had to resort to using such a backdoor-way of finding out something so important to her.

It did seem like the majority of my students didn’t know what they wanted to do in life. I assured them that life is circumstantial, and they would find the right path more or less by stumbling across it. My students, being art majors, were in a particular quandary because even if they knew they wanted to pursue an artist’s life they needed to figure out day jobs to maintain themselves. Professions in the arts and liberal arts do not come with a directed path the way medicine, law, or accounting does.

In truth I think the majority of people find it hard to “figure out” what they want to do, in part because the brain isn’t the right organ to consult — or I should say — the brain is probably good at figuring it out if your path is straightforward — like —”I think I’ll go to Law School,” but not so good if your options are wide open. It’s no wonder that for multiple millennia young people tended to follow professionally in their parents’ footsteps. First because they had a way in, they had a sense of what was involved in that line of work, i.e., if it was farming, they grew up on a farm doing farm work. In those days it was probably easier to figure out that you didn’t want to enter your father or mother’s trade— to be a coal miner, a grocery clerk, a seamstress, a washerwoman, a milliner, a clergyman, a financier, or whatever.

But in our day, white collar jobs don’t involve working with your hands or using your body; they are usually some form of office work, and what exactly people do in offices is pretty opaque.

Why is it so hard to think through what path you should take in life? I think part of it is that school learning does not teach you to value or possibly even recognize the skills you have. Students have a very narrow way of viewing their skills, for example, they invariably overlook their personal skills — being organized, being outgoing, being good with people, being efficient, being good with money, being able to do public speaking, having patience, having an eye for detail, being able to organize people. Whether you succeed at a job relies at least as much on these personality qualities.

An artist friend of mine, Carmen Lizardo, tells an amazing story. She was born and raised in the Dominican Republic and came to the U.S. after high school. Before applying to college, she went to the Brooklyn Library and took an aptitude test. Her results came out: artist, artist, artist. Carmen knew nothing about art; curious, she went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art — the first art museum she ever entered — and she knew immediately that this was the world she wanted to inhabit. Indeed, she has turned out to be a wonderful artist.

I would love to get my hands on the aptitude test she took. It seems like every kid in school would benefit from taking such a test.

Saturday, September 26, 2020

A gripe I have with the public education system is its misguided reverence for book learning over hands-on learning. Book learning treats students as if everything important about them exists only from their neck up.

Embodied learning is at least as important, if not more so, than intellectual learning. There are two distinct ways of learning —academic learning that feeds information directly to the brain, and embodied learning which is used to acquire physical skills. Athletics and visual and performing arts are generally taught in gyms or playing fields, in art studios, and in conservatories.

A toddler does not learn to crawl or walk by being told how to crawl or walk. A toddler learns to crawl or walk by crawling or walking, just as a singer learns to sing by singing. Embodied learning is a more complex, more holistic route to knowledge, one that is less directed by the brain, more directed by the body. The two paths to learning are fundamentally different. Book learning is verbal, logical, and slow; embodied learning by-passes the logical brain and coordinates instinct, intuition and the body.

One example is the basic mammalian instinct to suckle: a kitten or a baby does not have to be taught to suckle. Locomotion is also instinctual — a baby abandoned in the wild, if she survives, will not remain on her back. By herself she will learn to turn over, crawl, walk, and run. We are born with these types of instincts — something we knew to do before we developed language. In this way we can say embodied learning is a more fundamental route to knowledge than verbal or textual learning.

This is not a topic I might have given much thought to had I not taught studio art for three decades. As an experienced teacher, I found myself constantly advising my students to “Stop thinking!” — explaining that their minds cannot solve whatever problems they were facing with their artwork — that only by doing, by trying things out physically would they find a way forward. This was news to them: a lifetime of education had taught them to value their thinking above all else.

According to Wallace Stevens, unlike the body, the brain is never satisfied. If we eat our fill, we stop being hungry, after a good night’s sleep, we feel rested and energetic. This is not the case with the brain: our brains know no limits; it constantly wants more. Our brains also lie. I subscribe to the edict “Don’t trust everything you think.” The brain is not to be trusted. But when we feel pain, have an upset stomach, or run a fever, we know it’s true: the body doesn’t lie, nor does it get caught up in fantasies, entertain illusions of grandeur, or do any of the other suspect things that our brains are constantly doing.

I will elaborate on this topic in the next posting. In the meantime, I leave you with this factoid: A Silicon Valley executive once said that he will not hire computer programmers who have never worked with their hands; he claimed that people who have failed to acquire hand skills cannot think in certain ways. (You know what they say: muscles that are not used atrophy.)

Wednesday, September 16, 2020

I have fallen well short of the goal I had when I started this blog of posting once a week. I’ve been feeling like I don’t have that much to say. I considered giving up the whole thing, but recently I figured out there is something I can talk about almost endlessly, since I’ve been doing it for the last 30 years, week after week, in my role as a college painting and drawing professor.

To teach well you need to break topics down into components, or graduated steps that students can follow. When I started teaching I noticed there were things I could do, yet could not explain how I did them; I noticed I operated on a series of (almost) subconscious assumptions that needed to be closely examined; and I noticed teaching exercised skills that I had but had no occasion to use in my normal life. Ultimately teaching grew very rewarding for me because it employed many more of my capabilities than I had ever had opportunity to use before.

Recently I sat down, and in five minutes, came up with a list of a dozen topics I could write about. They included:

- Cerebral learning vs. embodied learning

- The advantages of painting and drawing in being immediate and extremely flexible mediums

- What “process art” is about

- The counter-intuitive fact that 2-D painting and drawing mediums have surpassing capabilities to evoke space compared to 3-D mediums, including film and installation

- The difference between narrative and non-narrative art

- The difference between using symbols vs. inference in art

- The basic difference between believing your body vs. believing your brain

- The argument against an academic art education

- The importance of Formalism as taught by the Bauhaus

- The particularity of individual color sense

- Why I distrust Theory (capitalization mine)

- Why my students thought I could read their minds

- The importance of visual thinking — focusing on Einstein as an example. (Admittedly I would have to do a fair amount of research to carry out this topic.)

I promise to cover each of these topics, in no particular order, in upcoming blog postings. But I revoke my promise to post once a week. I think once every three weeks is a more realistic goal.

Wednesday, August 19, 2020

My friend, Janet Zweig, sent me a link to a July 29, 2020 New York Times Magazine feature about swifts, birds that are known to stay airborne for as long as ten months at a stretch. It was written by Helen Macdonald, author of the memoir, H Is for Hawk. The article is so beautifully written it is almost transcendent, and does absolute justice to the subject, an otherworldly creature.

According to Wikipedia, swifts belong to the same family as hummingbirds and share the unique ability to rotate their wings from the base. Swifts and swallows look similar, but according to singita.com swifts are usually black and white or grey in color whereas swallows often have a russet color on their heads, throats, or rumps. Swallows can also be distinguished by an iridescent blue that appears on their wings and backs.

Swift in flight.

Swift in flight.

Swallow in flight.

Swallow in flight.

Swedish researcher Susanne Akesson, said in National Geographic, “They feed in the air, they mate in the air, they get nest material in the air.” Because their wings are so long and their legs so short, “they can land on nest boxes, branches, or houses,” but due to their built they can’t really land on the ground, nor are they able to take off from a flat surface.

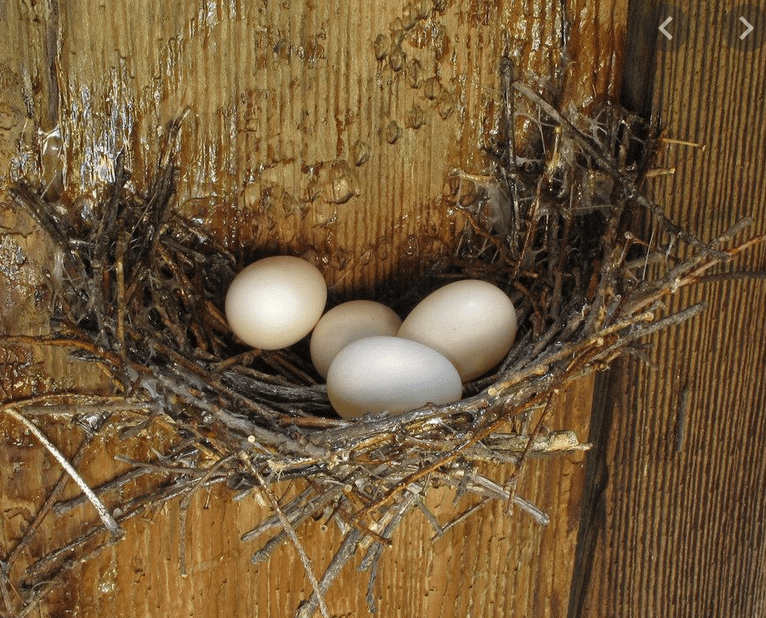

Their nests, which they like to build in obscure, dark and hard to reach places, are bonded together and attached to vertical surfaces with their saliva. The nests can be found in building hollows — under tiles, in gaps between windowsills, under eaves, and within gables.

Two swift nests attached to wood surfaces.

Two swift nests attached to wood surfaces.

Swifts mate for life, and they are long-lived. They start to breed at the age of four and typically live another four to six years. One swift was documented to live to the age of twenty-one.

Except during breeding season swifts tend to not land at all. They may have adapted their habits to match their feeding needs: their main source of food is high altitude insects: when hunting they store the insects in a special pouch at the back of their throats. The food is bound into a ball with their saliva; they may bring it back to their nests, or save to eat later. Once their broods are tipped out of the nest, the swifts never return. They travel in groups and can ascend as high as 10,000 feet. They fly so high they can orient themselves visually by looking down.

Chimney swifts.

Chimney swifts.

According to Wikipedia, “They often form ‘screaming parties’ during summer evenings, when 10–20 swifts will gather in flight around their nesting area, calling out and being answered by nesting swifts. Larger ‘screaming parties’ are formed at higher altitudes, especially late in the breeding season.

White-throated swift.

White-throated swift.

Swifts make massive ascents each day, once at dawn, and once at dusk. One researcher speculated that maybe “this is when they sleep… they take power naps by gliding on the way down.” [newscientist.com]

A swift was recently recorded to be flying at the speed of 69.3 mph. “And in a recent study, one of the tagged birds soared 40 miles without a wing-flap.” [Merrit Kennedy]

Swifts come in a range of sizes from the pygmy swiftlet that weighs less than an ounce, to the purple needletail that weighs 6.5 oz. The common swift weighs about 1.3 oz.

This is the link to the Helen Macdonald article, (https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/29/magazine/vesper-flights.html)

Friday, July 31, 2020,

Last month I listened to an audiobook by an astrophysicist, Max Tegmark, called Our Mathematical Universe, that I can’t get out of my mind. People say we are living in the Golden Age of Space Exploration, but I personally have not been paying much attention. This book, however, is so well written and accessible, it is like a primer for the uninitiated.

Did you know that space is infinite? Max Tegmark says that it is. I find this almost unimaginable — how can anything be infinite? And this infinite space is currently expanding, in the sense that things are moving farther and farther apart. Scientists document this by looking into space, which is the same as looking into the past. Things are so far away it can take millions of years for the light to reach us. The measure between forms decreases the farther away it is, and this increase of distance as it gets closer to us records the expansion of the cosmos.

The creation of everything that now exists happened about 13.7 billion years ago when the Big Bang occurred. We think of the Big Bang as the start of everything, but Tegmark, cautions that the Big Bang, instead of being the beginning of everything, may actually have been the end of something.

Did you know that 85% of the matter in this infinite space consists of dark matter? Dark matter isn’t dark — it’s invisible, and passes through everything, even us. Dark matter cannot be found within the electromagnetic spectrum (EM)]. EM radiation is energy that travels and spread out as it goes; the lamp by your bed side or radio waves are examples of EM radiation. Dark matter does, however, have mass: it accounts for about a quarter of the mass in existence. Scientists study dark matter by looking at the effects it has on visible objects. Dark matter and dark energy are the yin and yang of the cosmos. Dark matter causes attraction (through gravity) and dark energy produces a repulsive force (anti-gravity — it is the force that is making the cosmos expand over time). The visible world, that is, matter that we can see, accounts for only about 5% of the matter in space.

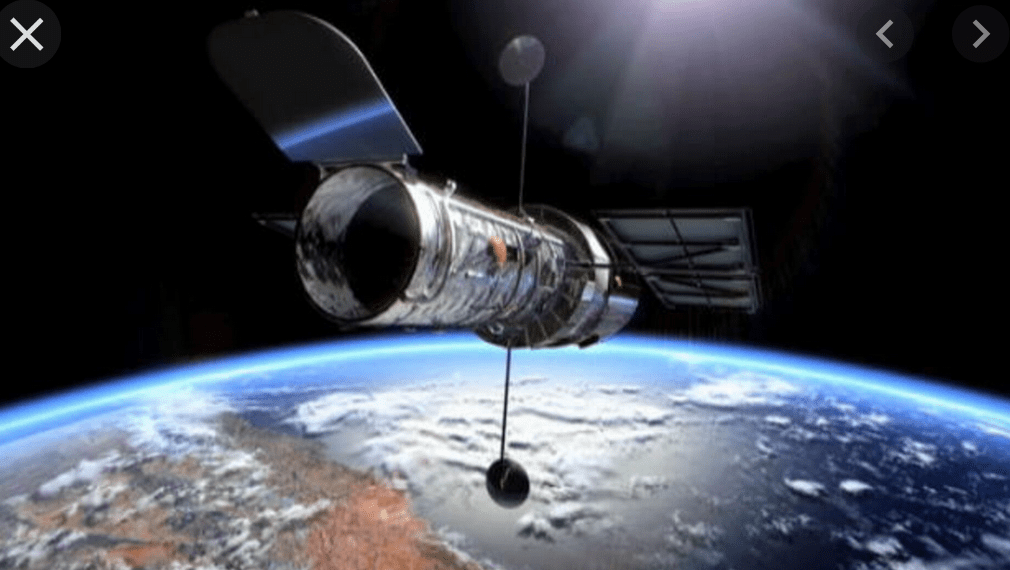

Much of what we know has been discovered through the Hubble space telescope. This is an image of the Hubble telescope. And the two images below were taken from it.

This is apparently a quasar, which are ultra-bright cores of distant active galaxies. An outflow like this one from a quasar functions like a tsunami in space, wreaking havoc within its galaxy.

This is apparently a black hole. Who knew black holes were so beautiful?

I followed along with the book pretty well until about half-way through, when things got difficult. Since it was an audio book I had to re-listen to passages two, three, sometimes four times before I felt like I could move on; the second half of the book is mind-blowing.

Tegmark maintains that we can no longer talk about the universe because it is believed that ours is only one universe out of an infinite number of universes, which is referred to as the multiverse. So far so good. But then the author starts talking about parallel universes.

There are at least five theories why a multiverse is possible, and Tegmark, pursues this line of thinking.

- No one knows what the shape of space-time is, but one prominent theory says that it is flat and goes on forever, which presents the possibility of there being many universes out there. But particles can only be put together in so many ways, which means that within infinity, things would have to start repeating.

- There is a theory of “eternal inflation” that says when looking at space-time as a whole some areas of space stop inflating, like how the Big Bang inflated our universe, but other areas of space will keep on inflating. This is visualized as a series of bubbles. We are in one bubble, but there may be another bubble just beyond ours that exists but is not connected to us. In this and other subsequent bubbles (universes) there may be laws of physics different than our own. Max Tegmark believes there are at least three levels of universes, but probably more.

- Following the laws of how subatomic particles behave (quantum mechanics) there would be a range of universes.

- Now we come to mathematical universes (which explains the title of Tegmark’s book, Our Mathematical Universe). The structure of mathematics may change depending on which universe you live in, and Tegmark says there is at least one purely mathematical universe “that can exist independently of me that would continue to exist even if there are no humans.”

- And finally, parallel universes: Going back to the flat conception of space-time, the number of possible particle configurations is limited to 10 to the 10th power to the 122nd power worth of possibilities. In an infinite space, with an infinite number of cosmic patches, the particle arrangements within them must repeat an infinite number of times. In this scenario there is a universe out there exactly like ours containing someone exactly like you.

Finally, let me leave you with one more thought, something that Einstein believed — that time is an illusion — it is just a very persistent illusion.

Thursday, July 24, 2020

I have been designing and installing public art for almost twenty years. I remember because my first and second public art projects were delayed and affected in different ways by the occurrence of 9/11. Security at the Seattle-Tacoma Int’l Airport had to be rethought and reconfigured, pushing back the installation schedule of the mosaic columns project from 2001 to 2004. The other project, at P.S. 58, a pre-K to 9th Grade school in Maspeth, Queens, was renamed The School of Heroes because Maspeth was the home of two Fire Stations, one of them a Haz-Mat Unit, that suffered big tolls in casualties on 9/11. My commission was to install painted panels in the Auditorium; I ended up using the two large panels on either side of the stage to depict scenes referring to 9/11.

I bring this up because I am a finalist for a project in New Jersey that has me doing something I have never done before. I have always known that my studio work and my commission work live in very different parts of my brain. They use different skills: the studio work — painting and drawing — is an intuitive, searching process where most of the time I do not know what I want or where I am going: I simply follow my nose. Because my work is so process-driven I start my paintings and drawings with almost no idea of what I want to do. All the thinking and planning occurs on the surface of the artwork. I add, sometimes I subtract, but the work is built overtime in layers.

The commissions are very different; they are designed with specific things in mind. For example, the budget is the first thing I consider because it determines what I can afford to do. Materials and fabrication costs vary greatly; anything that is handmade is expensive, whereas processes that can be machine made or programmed into a computer, are much more affordable. I am also guided by a site, a space, a size, and an anticipated audience. In the commissions I borrow from the visual vocabulary I have developed in my studio work. The fun of doing a commission is being able to translate my visual language into different materials, at times build them in monumental sizes, and I end up with a permanently installed artwork that lives in public.

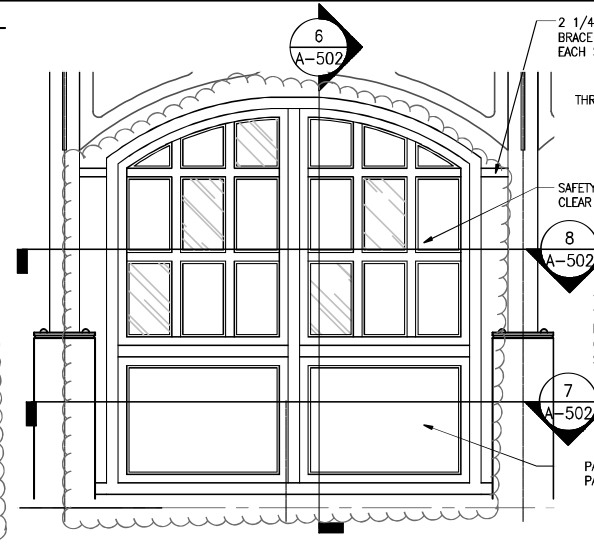

The New Jersey project involves designing laminated glass that will fit into windscreens like this drawing. Architecturally speaking, these are quite elaborate windscreens that look and feel like formal double doors or stately arched windows. But they are in fact what they claim to be, windscreens located in the open air at above ground train platforms.

I was quite intimidated when I first realized that this was the structure I had to design for. To have to consider how the arch and the partitions would affect a composition seemed complex and the notion that I had to come up with a total of seven designs in a month or less seemed overwhelming.

Then I got a bright idea. I decided to see what it would look like if I took some of my current gouache and oil marker drawings and inserted them in.

I quite liked the effect

Wednesday, July 15, 2020

I am going to address the development of my recent studio artwork. I knew by mid-2018 that the Mandala paintings I had been producing since 2011 had come to an end. When I was a young artist, the end of a series caused me great distress; I had a bad habit of wanting to hang on, to try and extend the life of a series. The trouble is that, as artists, we don’t have that much control over what we do — the artwork has a life and will of its own quite separate from the will of the artist. You know a series is at an end when the interest, excitement, sense of exploration is gone. Refusing to acknowledge this fact leaves you stuck in place, making weaker and weaker work.

Many Chamber, oil on canvas, 48” H x 72” W, 2015

This painting, Many Chambers, is for me a high point of the Mandala Series. The Mandala series, was my attempt to bridge — for lack of a better term — my conflicted ethnic identity. I knew that my visual aesthetics was rooted in Eastern Art, in the Middle Eastern and Far Eastern love of pattern and decoration; as opposed to Western Art and its roots in a Greco-Roman tradition that emphasizes the human figure and man’s centrality in the world. The Mandalas allowed me to use an iconic circle, or circles, within a rectangle that I could “decorate” to my heart’s content. In doing so I could draw as much as I wanted from Western art traditions. In Many Chambers, I added pearls, lace, and references to Medieval shields.

When I moved to New York City in January 2019, I was fortunate to have a three-month Artist Residency at the Carter Burden-Covello Center at E. 109th St. I spent months flailing in the studio trying out different mediums. Nothing worked until looking at architectural and perspectival diagrams, I got an urge to make linear compositions using oil markers, and traditional drafting tools like rulers, compasses, and trammel points.

North Star, oil and oil markers on canvas, 30 x 30”, 2019

The painting, North Star, is emblematic of the work I was making at the end of my three-month residency. What this transitional body of work made clear to me is that I absolutely did not want to rely on the use of symbols. I have relied on symbols in my work since forever. I was finally ready to admit to myself that I did not believe the symbols I have been using. In North Star I rely on the symbolic use of “the heavens” by employing a sky background and planet-like globes.

Untitled 2019-14, gouache, oil, oil markers on paper, 6 x 9 inches, 2019

It was in the following two months that the work in the studio cohered for me. I left off working on canvas and began to make small drawings with gouache, oil, and oil markers, which began rather mandala-like until they became more spatial.

Untitled 2019-22, gouache, oil, oil markers, 6.75 x 10 inches, 2019

Perhaps I need to explain the difference between “symbols” and “inferences.” The current work, although abstract, sometimes infers space, globes, sky, etc. but they are not symbolic because the artworks do not live or die depending on the “meaning” of any symbol. The artwork succeeds on its own terms — without relying on exterior meaning.

I came to perceive the 2019 drawings in the aggregate to be focused on the slow process of unveiling, recognizing, seeing, knowing and understanding.

They speak to the presentation of the self. People are complex, layered: we are comfortable with certain aspects of ourselves which we foreground or project outwardly; keeping in the distance, obscured, layered — aspects of ourselves that feel more tender, vulnerable, private. Perhaps because I am aware of this tendency in myself, I saw the layering, the veiling, as choices we make in what we reveal, how much, and when.

Alternately the drawings can be looked at as being about the time it takes to acquire knowledge, information, acquaintanceship. We are taken in by the large, bright, obvious aspects of people and things. Truly getting to know somebody or something is a slow process. We are often fooled by the presentation — people, after all, are known to lie to themselves; thus it takes time and we discover things in layers: it takes discernment and long exposure to perceive the deeper truths.

The drawings from 2020 are related to their predecessors yet seem different. I perceive a more concrete and focused presentation of the environment. Instead of being focused on objects in space, the specificity of each environment/situation dominates each picture.

Untitled 2020-06, gouache, oil markers on paper, 8.75″ H x 11.75″ W, 2020

It was not until this drawing, Untitled 2020-06, appeared that I began to read the series as focusing on navigation within constraints. We have to abide by the laws of nature and the laws of man; we are all socialized to live within society, to play by the rules. Although we live within guardrails, it is our job to navigate a personal way of going through life, of being in the world that gives us enough flexibility to be ourselves, to fulfill our needs, to accomplish our personal, or societal goals. I think these works reflect this particular aspect of the human condition — of the need to learn how to flourish within constraints.

Wednesday, July 8, 2020

The first (and only) blog I kept was in 2017 chronicling the months I spent in the Far East. I wrote the blog more or less as a record for myself since I didn’t expect anybody to read it, although I came to learn that many friends and family did.

My excuse for starting this blog is that in the midst of the pandemic, I spend a lot of time alone, and talk to few people. To break out of my isolation I decided to keep a weekly blog — that means one entry a week — nothing that will strain either me or my readers — should there be any…

To locate myself I took a selfie in front of my Upper West Side apartment building where the Cafe Luxembourg is located.

This is my subway, the W. 72nd St. 1/2/3 train station. Note how eerily empty the street is.

This is the exterior of my Brooklyn studio building, located near Graham Ave. on the L line.

My corner of the large studio I share with four other artists.

The messy table where I work on my gouache and oil marker drawings.

See a Map of my work on Wescover!

See a Map of my work on Wescover !

Learning to See: A Fulbright Semester Teaching Painting in Beijing

Amy surrounded by her Graduate Painting students at Renmin University of China, Beijing, Spring 2017

Learning to See:

A Fulbright Semester Teaching Painting in Beijing

I share below an essay I wrote about my Spring 2017 Fulbright semester teaching at the Renmin University of China’s Graduate Painting Program. This essay has been published by Routledge Press in a book titled Inquiries from Fulbright Lecturers in China: Cross-Cultural Connections in Higher Education.

I had a wonderful time in China, I made friends, I spent time with my Chinese relatives, I traveled widely within the country lecturing at different universities and art schools — I learned A LOT.

If interested you can read my essay below.

I.

I spent the spring of 2017 as a visiting professor in the Graduate Painting Program at Renmin University of China in Beijing. I was born in Taiwan, immigrating to the West with my family at age 4. My parents grew up in China, and we spoke Chinese at home. But despite being ethnically Chinese, I experienced two cultural gaps while teaching in China, the first one in the student-teacher relationship and the second on the subject matter of the course.

My Chinese students’ ability to understand English varied widely, but they all had handy Chinese-to-English translation apps on their cell phones. I depended on my MacBook Air as an essential teaching tool, since my Chinese vocabulary is limited to the domestic and quotidian; I carried it with me everywhere and relied on Google Translate. I would type out entire paragraphs; if the translation came out garbled, they would let me know and I would rephrase and try again. I made myself available once a week for studio visits with students not enrolled in my class; in this way, I was able to meet other art students, both graduate and undergraduate. I also took interested students on field trips to art openings, exhibitions, and studio visits.

To my delight, the Chinese have no difficulty understanding that I — who look just like them — am American. When I travel elsewhere in the world — Egypt, Italy — people sometimes have a hard time grasping this concept.

When we went out together, the students had an endearing way of offering to carry my things — coats, bags. Since Beijing is extremely dry, they were attentive in offering me tea and bottled water. But the incident that completely disarmed me happened at a class party I hosted in my apartment that devolved into the playing of games, games that were like rowdy versions of “Simon Says.”

At semester’s end, the students organized a potluck dinner in the graduate painting studio. When I arrived, one of the students handed me a bag of gifts — an ingenious eyebrow pencil and shaping knife, which she promptly

proceeded to demonstrate on me and on her classmates. (The shaping knife was used to eliminate stray or excess eyebrow hairs. The eyebrow pencil, with its three component parts, was used to delineate a contour line around the eyebrow, fill in color to get consistent coverage, and as a final touch, had a small bristle brush for separating and combing the eyebrow hairs in upward strokes.) Some days earlier I had complimented the student on her eyebrows — Chinese women are particularly attentive to their eyebrows, which are traditionally seen as a focal point of beauty. After dinner we settled down to playing round after round of the parlor game Cops and Assassins.

Compared to the Master of Fine Art (MFA) students at the State University of New York at New Paltz where I have taught for two decades, the Renmin graduate students seemed — not young in the sense of being immature — but somewhat naïve. They are younger — most of them enter the graduate program directly out of college, whereas the majority of our MFA students have had some life experience. Returning to school the American students know that spending two-years immersed in a fulltime graduate art program is a privilege; most of them pay for their own education, often with student loans. They also clearly understand that once they graduate, in spite of having an MFA degree, like most artists, they will have to take up a day job; whereas my Renmin graduate students seemed to entertain vague ideas about life after school, a condition I associate more with undergraduate students. In China students who attend public universities like Renmin pay minimal tuition; they cover their own living expenses, but those costs are also modest. [1]

I was keenly aware of my lack of knowledge and understanding of how Chinese society functioned. In the U.S., although it is helpful to have connections, you do not have to be connected to get a job. In China, I noticed that a lot of my own Chinese cousins’ children had “inherited” jobs from their fathers. That is, if their college studies related to their fathers’ they would gain entry into the firm — especially if the jobs were governmental (in schools, hospitals, or city government); a couple of my cousins literally vacated their positions to their offsprings by retiring.

From what I could tell none of my students came from artistic backgrounds; they were clearly striking out on their own. A couple of them were or had been primary school art teachers, and the master’s degree will qualify them for high school teaching. In the U.S. the MFA is a terminal degree. It qualifies you to teach at the university level. Currently in China, you need to have a Ph.D. to teach at a university, although it is not uncommon to be hired with a Master’s Degree, and be given a period of time to complete a Ph.D.

Life in China for the Chinese is complicated by the Hukou, a kind of passport system that restricts access to government-funded services (like education and healthcare) to the birthplace of the holder. A Chinese citizen cannot relocate at will. A provincial student gets access to residence in Beijing if they are accepted into a Beijing university, otherwise a person can only legitimately move to another city if they gain employment in that city. Residency in Beijing is highly prized because the city offers more employment opportunities, and because it is urban and culturally sophisticated.

I asked some of the students why they chose to attend Renmin University and was surprised when all but one of them said they had come because of their professor. (They met the professor at the university in their home Province; when the professor joined the Renmin faculty, they followed them to Beijing.) I asked Yaning, the student who entered Renmin without a professorial connection, if knowing a professor increased the likelihood of getting accepted to the college, and she replied with an emphatic “Yes!” Renmin University is prestigious and entry is highly competitive: it took her two tries to get accepted. She also said that in China you cannot enter a Ph.D. program unless a professor agrees beforehand to be your advisor, and professors only take on two advisees a year.

Prof. Guo Chunning, a Renmin Art Department colleague, said that a close connection to a professor benefits a student because university professors can be well connected, and in China many art positions and opportunities are governmentally funded. Lest I sound judgmental or sanctimonious, let me admit that there was a time not so long ago in the U.S. that art department teaching jobs were handed out in similar ways. For decades if you graduated with an MFA from Yale you were almost guaranteed a college teaching job, and the alums laughingly referred to “the Yale Mafia” for the number of prestigious art prizes, like the Tiffany or the Rome Academy fellowship, won by the MFA alums. When I was hired into the SUNY New Paltz Art Department in 1997 one of the older art professors off-handedly asked, “Who does she know?”

II.

The larger cultural gap I encountered in China involved teaching. I developed a deep attachment to my students; but I came away confused by what I considered to be strange gaps in their education — by their inability to do certain basic tasks or perceive and articulate some elemental visual aspects of two-dimensional composition. My class at Renmin University was made up of graduate students majoring in “Western” Painting as well as “Chinese” Painting — in China they are seen as separate disciplines.

For an artist like me, who has spent most of her painting career working with a visual vocabulary inspired by Middle Eastern and Far Eastern art, it was with interest that I came to realize while in China that my students did not know what to make of my layered, highly patterned mandala-like paintings. My most advanced graduate student, Hong Xing, admitted to me that he found my work to be (only) decorative.

One of the lectures I gave when I traveled across China was titled Double Vision: Reconciling my Eastern Visual Sensibility with a Western Art Education. In the lecture I posited that Western art tradition, which descends from Ancient Classical Greek and Roman art privileges man, or at least the human figure, as centrally important. This viewpoint differs distinctly from Middle Eastern and Far Eastern art traditions that do not fetishize the human form — except in the guise of the Buddha or the Gods.

In a Chinese ink painting a figure, a house, or a bridge, is gently inserted into the landscape, occupying no more, and usually less, visual importance than a tree, a hill, or a body of water. The same applies to built pavilions, pagodas, and bridges that are designed to blend in with, not dominate, the landscape. Contrast this with the imposing roads, bridges, aqueducts, temples and amphitheaters the Ancient Romans constructed across Western Europe.

Chinese landscape painting, also known as Scholar Painting, was historically a refined and elitist art form practiced by noblemen and the literati. It was never an art of the people. The popular or commonplace art — porcelain wares, tiles, bronze vessels, cloisonné, or fabric design — in China, Japan, India, and the Middle East tended to be bright, colorful, patterned, and ornamented. What underlies public or popular Middle and Far Eastern art is a more decentralized, dispersed conception of the world that is consistently and insistently conveyed through the use of repetitive patterns. Visually this kind of repetition flattens hierarchy: what you sense is a pervasive, consistent, almost hypnotic evenness. No one component is more important than another, including man. And it is from this more popular and utilitarian art that I draw inspiration for my work.

European art with its dominant Classicism has not marched forward uninterruptedly in the West. There have been, in fact, two distinct periods when it fell out of fashion. The first occurred in the Middle Ages, starting with the Holy Roman Empire when the flatness of Byzantine art overtook the Classical; in fact, for hundreds of years the technique of Classical rendering was forgotten and essentially lost until it was revived in the Italian Renaissance. The second period of time when traditional Classicism was set aside in the West happened in the first half of the twentieth century with the advent of movements such as Cubism, Surrealism, Abstraction, Dada, Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, Land Art, and Color Field Painting.

It is this second period that is relevant to this discussion. I will show how China’s adoption of Western Painting was indelibly affected by a twist of historical fate that prevented the Chinese from undergoing and experiencing Modernism as it unfolded in the twentieth century.

III.

Like Russia, China in the 1910s experienced staggering political change. The Qing Dynasty was overthrown in 1912; revolution was in the air, and “reform-minded Chinese debated how to modernize their nation.”[2] Chinese scholars left to study abroad; in the 1920s and 30s Paris received two waves of Chinese student-artists. (A number of Chinese artists were accepted into the Académie des Beaux-Arts, and a large survey of work by Chinese artists in Paris was commemorated by an exhibition at the Jeu de Paume.)[3] Although some of these artists remained in Paris, the majority returned to China, bringing with them the new medium of oil painting. In 1949, after the Japanese were expulsed, and the Kuomintang government routed to Taiwan, the Communist Party took control of China. For the next thirty years, until the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, China would be closed to the West.

By 1949 – 1950 the USSR had become China’s closest ally. In the summer of 1949 a delegation of Chinese Communist Party leaders traveled to Russia to confer with Stalin and the Soviet leadership. The delegation stayed for three months and made a series of requests of the USSR for financial and educational aid. In a July 6, 1949 letter to Stalin, the Chinese asked to be allowed to study Russia’s public administration, requested Russia’s help in developing postal, telegraphic, and air service between the two nations, asked Russia to train the Chinese Navy and Air Force (including the building and repairing of aircrafts), and expressed the desire to establish a closer cultural relationship with the Soviet Union. [4]

Today, just as there are scattered remnants of Soviet-built industrial structures across China — such as the East German factories now occupied by art galleries in Beijing’s 798 Art District — there remains in China, less visible, but possibly more deeply embedded, systems acquired from the Soviets — and the Chinese system of art education is one of them.

IV.

Currently in China children who are interested in art are taught to render realistically from life. The Chinese have adopted wholesale the tradition of Western art as it was inherited from Ancient Classical Greeks and Romans, and their understanding of space is grounded on the Italian Renaissance discoveries of one- and two-point perspective.

Prior to my semester in Beijing, I had encountered only one student from Mainland China. Mei had completed a Master of Art in Painting at another American university prior to entering our MFA Program. Despite that experience, she stubbornly held to certain notions about contemporary painting that conflicted with our understanding on the subject. In the current art world anything goes: work can be figurative, abstract, illustrative, political, material, conceptual, narrative, appropriated. There is no one dominating movement or medium: all approaches and media are seen as equally valid.

It was disconcerting to have Mei insist that she wanted to make “modern art” because that turned out to be a series of acrylic wash paintings on large sheets of paper with a loose, clumsily painted female figure immersed in water. She seemed to believe that rendering the figures badly was precisely what made her work “modern” and expressive, which struck me as a superficial and simplistic, not to say misguided, approach to abstraction.

I had a similar experience at Renmin University, where I met an oil painting graduate student, Yu Chun, who had a gift for figurative work. He wasn’t just good at rendering figures. He had the ability to make his figures unusually expressive, yet he insisted that he did not want to paint representationally. He wanted to make abstract paintings. He showed me painting after abstract painting he had started and abandoned: clearly he was having difficulty moving forward.

Encouraged by Fulbright, I crisscrossed China lecturing at universities and art academies, getting glimpses into a wide variety of art departments, among them three of the six Chinese Art Academies, all impressively large, newly constructed campuses where an entire multi-story building housed a single discipline, like sculpture — quite a contrast to a vocational college in Hangzhou that offered a much shallower art education, where teaching a discipline such as ceramics is crammed into six short weeks of study. One of the more interesting places I visited was Xinjiang University in Urumqi, Capital of the Uyghur Autonomous Region where the Art Department only offered two disciplines, Graphic Design and Fashion Design. My hosts were two professors, Ablat Boshi, an ethnic Uighur, and An Xiaobo, an ethnic Manchurian.

Prof. Ablat and his wife had traveled to the U.S., where they toured art museums. Back home, he wanted to make abstract paintings. (He did his graduate studies in the former Soviet Union; prior to this he had painted portraits and landscapes.) He said, “Representational painting is of the past; abstraction is today.” Looking at his paintings I could see that he, too, was hitting a roadblock with his work.

I am sympathetic to these painters, not because abstraction is more current than representation but because being able to perceive and understand abstract visual language is essential to understanding contemporary visual art. A prime characteristic that runs through most Modern and contemporary art is that the work is undergirded by abstract qualities encapsulated by what we call Formalism. Formalism is based on the relationship between the abstract elements of art, which consist of color, value, line, form, shape, space, texture, and pattern.[5]

The main difficulty for realist artists moving into abstraction lies in the need to negotiate a different sense of space. An artist who has only learned to paint representationally can perceive perspectival space, overlapping space, and stacked Chinese painting space, but she does not know how to see in terms of abstract space.

Of course, every artist works with the elements of art, but when you work abstractly, that is, when you take away the “thingness” of the subject, you automatically change the nature of the space in the painting. Without “things” (like a person, a stand of trees, a bowl of fruit) there is no need for a “realistic” sense of space, the laws of gravity need not apply, nor do we insist on having a unified sense of light. The paradigm shift is so extreme that unless the artist has been taught how to see abstract relationships, she will be lost; the traditional bearings she has always relied on are missing.

This was the condition of my former student Mei and the two painters I met in China. I knew they were failing to understand something, but I did not know what it was. Only after returning home, where I sought out Mei, exchanged texts with Prof. An Xiaobo of Xinjiang University, and queried Maxine Leu, a New Paltz graduate student from Taiwan, did I finally dig down to the root of the problem.

In one form or another college level art education in the industrialized countries teaches the design principles on which Modernism is based. The Bauhaus School in Germany codified these design principles and established a Vorkurs (preliminary course) that taught students how to work with color, value, line, form, shape, space, texture, and pattern isolated from representation.[6] Also known as the International Style, Modernist aesthetics cuts a broad swath across the globe in architecture, graphic design, and much of industrial design and fine art. Because the Bauhaus was a school as well as an art movement, the faculty and students who fled Germany before and during the outbreak of World War II, taught Bauhaus-based education methods wherever they landed — in Europe and the Americas — but China and the Soviet Republics, cocooned in their self-imposed silos, were cut off from this larger artistic conversation taking place in the world.

Today, contemporary Chinese artists and art students are familiar with the history of Western art, including Modernism. Simply teaching Bauhaus design principles as theory in lecture classes, as it is currently done in China, does not work. Most art forms, like athletics, belong to a category of cognition known as embodied knowledge. Embodied learning is acquired only when the body and its senses are engaged, not just the brain. You cannot teach a person to sing by lecturing to them about singing; people learn to sing by singing. Learning to see color relationships, seeing the compositional interaction between positive and negative shapes, or understanding the spatial effects of color — must all be experienced visually, and the knowledge acquired physically, through trial and error.

Chinese artists who have not had the benefit of a Bauhaus-based studio education acquired their knowledge of Bauhaus principles only through book learning, so to speak; because they were not physically trained to work with the visual phenomena, they have not been sensitized and as a consequence they either do not see or do not look for their effects. Basically the art schools in China do not realize the importance of training students to use these principles in studio courses, and the faculty, because they themselves have not been trained, do not know how to teach it.

A consistent and notable thing I found with art students in China is how little they regarded space. Even students who were clearly working with a sense of landscape were at times unable to describe the space in their work. In China, working with the students, I kept coming up against what I can only describe as an astonishing level of space-related visual illiteracy. It was as if, in their art education, space was never discussed.

When I returned home and met up with my former student, Mei, I pointedly asked what she saw when she looked at the work of her MFA classmate, Brooke Long, who made architecturally inflected abstract paintings. Mei said, “I see color, shapes, lines, and rhythm.” I asked, “What about space?” She looked at me, tilted her head, and repeated – “Space?” – and blankly shook her head.

A year later in 2018, I returned to China and met with my former students at Renmin University. By then I had completed a draft of this essay and could tell them of my findings. The penny dropped when Yu Chun, the student who tried, unsuccessfully, to paint abstractly, admitted that he only considers the lateral space in his artwork, not the depth!

The two incidents confirmed what I had experienced in China. The students — whether they painted representationally or abstractly — were literally not looking at, much less giving consideration to, spatial depth in their paintings.

Ironically, it is in painting — a two-dimensional art form — that space is most present, most manipulated, most dramatic. Sculptures have bulk and sit in space, as do installation art, but they do not manipulate the space around themselves. Painting, on the other hand, using the magic of illusion, can flatten space, exaggerate perspective, deepen space, contort space, invent space, and spatially fool the eye. Most people, when asked, would probably say that color is what makes painting and drawing unique mediums, but sculptures, photographs, installations can also employ color; it is the possibilities of creating and inventing space that make painting and drawing singular.

VI.

It should also be noted that the Soviets did not aim to produce fine artists; they were training art workers. Art workers are distinguished not by a personal vision as much as by accomplished skill and craft. To produce an art worker you emphasize skill training, and Chinese art students are generally quite skilled. A sculptural course on the figure at a Chinese art academy might begin with students copying Roman busts and Renaissance sculptures before they go on to copy a wide range of ancient styles of Chinese Buddhist and dynastic sculptures. Chinese professors are conscientious about passing down traditions of fabrication. Skilled graduates from such programs of study are able to restore, repair, and imitate ancient artwork. To acquire this level of skill is arduous and time-consuming; it swallows up the majority of time and energy of a student undergoing four years of college.

In comparison, U.S. art education is usually less insistent on teaching skills. Skills are taught, of course, but at least as much emphasis is placed on helping the art student develop her individual voice, her subject matter and concepts. Without development in these areas it is hard for an artist to become self-actualized, and she is likely to remain a “mere” craftsperson.

This brings me to the most startling discovery I made while in China. It occurred around midterm when I scheduled a class critique. Arriving at the student’s studio, I was surprised and mildly annoyed to see she had not set up her artwork. I asked her to do so and was irritated by the haphazard way she proceeded. (Artworks are seen in context, and it is important how work is presented.) I moved things around and when the work was passably set up I turned to the class and asked them to start the crit. They looked at me in confusion, then at each other, which caused me to look back at them with equal lack of comprehension. It took a couple of beats before I caught on — the students did not know how to start because they had never held a class critique before!

Coming out of an American system of art education I was unable to conceive of this. In American pedagogy the class critique is how students are trained to “see.” Critiques discipline students to speak analytically about artwork because they are forced to articulate what they see and how they see. When the artwork of a particular student is being discussed, she receives feedback that allows her to hear how her work is being received, read, understood, interpreted or misinterpreted.

In his art blog Kurt Ralske explains the centrality of the group crit in American art schools:

The Crit

The word “crit” is not found in the dictionary, and is not used in normal conversation. But to those in art school, it’s a term that points to the center of the universe. Here, “crit” means the most essential and familiar of events: the critique session, in which a student’s artwork is formally evaluated by a group of faculty and students. A student presents his work, and the group responds with feedback: comments, questions, advice, cheers, jeers, and tears.[7]

The flip side of not integrating class crits into studio art courses is that, the professor, by default, becomes the single “authority” in the classroom since she does all the talking. The students are not given a structured forum that demands their verbal participation, their active engagement. This top-down aspect of art education reflects the top down structure of the Chinese and Soviet governments.

The regrettable result of not being trained to speak in class crits is that students are left unable to verbally analyze what they see. This was demonstrated to me at the end of the semester: I took some students to the Faurschou Foundation to see a small retrospective of paintings by the Scottish painter Peter Doig, which included Doig’s early paintings — the landscapes he made during and immediately after graduate school.

When we walked into the gallery, we immediately felt uplifted by the paintings; the students and I caught each other’s eyes, nodded, and smiled. As I stood in the first room surveying the paintings, my student, Hong Xing asked me:

“Are you able to say why a painting is good?”

I said, “Yes, I can. Why? Can’t you?”

He said, “No, not really.”

So I gathered the students in front of the first painting and “modeled” for them how I looked at the painting. I said, “These are landscape paintings, but they are not like any landscapes you have ever seen before, right? That the artist managed to do this is already remarkable. Landscapes have a very long tradition; it isn’t easy to bring something new to a landscape.” I then did a Formal analysis of the painting, talking about the visual effects Doig achieved and how he achieved them — the range of paint application, the layers of information the painting delivered, the variety and inventiveness of his visual vocabulary, and the spatial complexity of the painting. I then took them around the gallery doing the same with a few of the other paintings in the show.

That this occurred at the end of the semester was unfortunate and frustrating. I had been with these students for three months, but because their art training had been so different from my own, I was slow on the uptake. I had to hear, see, or experience a student’s inability to do something before I could perceive the deficit. This made me feel foolish and negligent as a teacher. But it wasn’t negligence; it was a failure of imagination on my part. Apparently I was so conditioned by the style and sequencing of American art education that I could not imagine a system that left out such important and fundamental art-teaching practices.

[1][1] Lim, Jason. “Why China doesn’t have a student debt problem.” Forbes, August 29, 2016, accessed September 30, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jlim/2016/08/29/why-china-doesnt-have-a-student-debt-problem/#3ce6c3641a58.

[2] “Pioneers of Modern Chinese Painting in Paris: Chu Teh-Chun, Lin Fengmian, SanYu, T’ang Hatwen, Wu Dayu, Wu Guangzhong, Xu Beihong, Siong Bingming, Zao Wou-ki,” deSarthe.com, May 12, 2014, accessed April 18, 2018, https://www.desarthe.com/exhibitions/pioneers-of-modern-chinese-painting-in-paris.html.

[3] McHugh, Fionnuala, “Exhibition illuminates Chinese artists who lived in Paris in the 20th century.” South China Morning Post, International Edition, November 1, 2017 accessed April 26, 2018, http://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/arts-culture/article/1526589/exhibition-illuminates-chinese-artists-who-lived-paris-20th.

[4] Heinzig, Dieter. The Soviet Union and Communist China 1945-1950: The Arduous Road to the Alliance. Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe, 2004.

[5] Morley, Simon. “In praise of vagueness: re-visioning the relationship between theory and practice in the teaching of Fine Art from a cross-cultural perspective.” Journal of Visual Practice, Vol. 16, No. 2 (2017) 87-103, February 23, 2017, accessed April 30, 2018, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14702029.2017.1292380.

[6] Morley, Simon. “In praise of vagueness: re-visioning the relationship between theory and practice in the teaching of Fine Art from a cross-cultural perspective.” Journal of Visual Practice, Vol. 16, No. 2 (2017) 87-103, February 23, 2017, accessed April 30, 2018, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14702029.2017.1292380.

[7] Ralske, Kurt, “The Crit,” KURT RALSKE (blog), May 2011, accessed April 26, 2018, www.retnull.com/index.php?/texts/the-crit/.

Asia Travelogue 2017

Asia Travelogue 2017

I was awarded a Fulbright Teaching Fellowship to China in Spring 2017. I used it as an occasion to travel thru Asia. My itinerary was to fly from New York to Taiwan where I would drop off my luggage, stay overnight, then fly to New Delhi where I would meet up with my Jean and Bernie for a two-week guided tour of India. From Delhi I would return to Taiwan for a ten-day stay, before flying to Lijiang, the capital of Yunnan Province in Western China for a week-long Fulbright Orientation. Only mid-way through the Orientation would I get my teaching assignment, which turned out to be at Renmin University of China in Beijing. At the end of the semester I met my friend Janet Zweig and two of her Brooklym friends in Tokyo for a two-week stay in Japan. If you scroll down you will catch the itinerary from back to front. If you care about chronology, it is best to scroll all the way down and read your way up.

Tuesday, July 11, 2017, Kyoto and Tokyo, Japan

On our last (partial) day in Kyoto Janet and I visited the Kyoto National Museum before heading to the Kyoto Train Station where we took the three hour ride to meet up with the boys in Tokyo.

The old and new wings of the Kyoto National Museum.

The Kyoto Train Station is a monstrously large complex made up of a shopping center, restaurants, hotel, and transportation hub. This is a Lego model of the station:

Janet and I found dinner in a basement floor dedicated to ready-to-eat food counters. I will end with a riddle, which one of these does not belong with the others?*

*Answer: The fish head what a photograph taken at Tokyo’s Fish Market. The other three are photographs of the amazing food on offer in the basement level of the train station department store. (I wish we had known about it earlier!)

For the sake of convenience Lee found us a hotel within Terminal 2 of the Haneda Airport that obligingly provided us with matching pajamas.

Monday, July 10, 2017, Kyoto, Japan

The Silver Pavilion, or Ginkaku-ji is a Zen Temple that was built in 1482 by a Shogun as a retirement villa for himself. He modeled it after the Kinkaku or Golden Pavilion, his grandfather’s retirement villa built at the base of the Northern Mountain. After the Shogun’s death in 1490 Ginkaku was converted into a Zen temple. Its garden is renowned for its sand cone sculpture, also known at the Moon Viewing Platform. It’s humbling to see how the East was practicing earth art long before Robert Smithson and others came along.

Another aspect of Japanese garden aesthetic seems to be their practice of exposing tree roots.

I can’t leave Japan without making note of their koi ponds.

The Japanese do something I have not seen in China. They cut written characters deeply into rock faces which, from a distance, has the effect of creating light and shadow within the strokes. This may also have been practiced in China, but at least in the 20th and 21st century it seems the Chinese carve into rock and paint the incisions with black paint.

We went in search of the Philosopher’s Walk, which I don’t believe we ever found. (Subsequently I learned from the internet that the Philosopher’s Walk is famous for being lined with cherry blossom trees, which happens of course only in the spring.) Along the way we did encounter some lovely walks and structures.

Sunday, July 9, 2017, Kyoto Japan

Quite coincidentally my cousin Zhengjiang and her daughter, Chenchen from Hangzhou, were also traveling in Kyoto, which made for a special and unlooked for occasion. In 1993 Janet and I traveled to China for the first time. I was on an Art International Travel Grant and we toured the country for five weeks, wherever possible meeting my father’s relatives in China. At that time Chenchen was four years old; now Chenchen is a young professional of twenty-eight. Here are the Then and Now photos:

The reunion takes place in a fancy Japanese tea and sweet shop.

Janet had read about “Owl Cafes” in Kyoto, so we go looking for one. It’s not exactly a cafe, it’s more like a cage-less owl zoo. We enter and are instructed on how to touch the owls (only with the back of our hands, and only on their backs). Our hands are sanitized with alcohol, and we are directed to stay clear of one particular owl who is “in training.” Sadly we note that the owls are all chained to their posts which makes it a mixed experience. (We liked seeing and petting the owls but we felt bad for their enslavement.)

We return to complete the tour of the Tofuku-ji Zen Temple gardens which we had started on our first full day in Kyoto and was was cut short for lack of time.

Saturday, July 8, 2017, Nara and Kyoto, Japan

We train to Nara. We stay half a day, first congregating with their famous tamed deer, then visiting the Todai-ji Temple with the Great Buddha.

The deer are regarded as sacred animals in the Shinto religion and they are everywhere. After the initial surprise of seeing them be unafraid of people the charm quickly wears off: living off tourists the deer have become conditioned beggars. (To prevent tourists from feeding them random food vendors make and sell digestible “deer cookies.” It is rather disconcerting to see the occasional overweight deer.)

The Todai-ji Temple which is dated from 728 is part of what was once one of the powerful Seven Great Temples of ancient Nara. Inside is housed the largest bronze buddha in the world.

This guy, you will note, is holding a brush and scroll. I don’t know who he is (his tag was not translated into English); my best guess is that he is Demon Guardian of Artists.

In the evening we return to our favorite restaurant, the Kamon. This time we arrive earlier and the tiny restaurant is full except for one small table which we squeeze into. We greet the chef and ask him to surprise us.

Small dishes begin to arrive one after another and we enjoy not knowing what is coming. The first night the dishes seemed like home cooking, but this time the cuisine is notched a level higher, and their sequencing is exquisite. It included a dessert like nothing we had encountered before: Janet and I loved it. Lee said he didn’t even understand what it was until the last bite; Sam gulped it down in two bites shocking me with what I considered to be his insensitivity. (I myself took tiny bites to prolong the pleasure.) I think the chef had meant it to be the last dish but Sam asked for one more. The chef didn’t break a sweat: out it comes, one last surprising dish.

This dinner cost three times that of our first visit: rightfully so, still a bargain. We bow and thank our way out. I catch the chef’s eye and mime clapping; such are the things you have to do when you don’t speak the language.

Friday, July 7, 2017, Kyoto, Japan

Kyoto has a famous, carefully maintained and cultivated moss garden boasting 120 varieties of moss. Accompanying the garden is the Nishikyo-Ku Zen Temple, also known as”Koke-dera” meaning “moss temple,” where we participated in a Zen ritual. Our attendance was pre-arranged by Janet who made a reservation; the price of admission consisted of an obligatory “donation” to the temple.

The ceremony was, as the Japanese are wont to be, formal and elaborate. Small stool-sized “desks” were arrayed in grid formation on the tatami floor. Each desk was lined with a piece of white paper; beside it lay a bamboo brush, a block of hardened ink, and a container of water. We were asked to kneel or sit on the flat cushions placed with each desk. We were each handed a small, bookmark-sized piece of smooth, stiffish, off-white paper. The Zen monk started chanting in Japanese accompanied by musicians on percussive instruments. At the end of the ritual we were directed to write down a wish, turn in the paper, and file out. (The Japanese all wrote out their wishes in beautiful calligraphy: we, the four American visual artists turned in our alphabetical scrawls.) I don’t know what they did with the wishes: I sort of assume they were later ritualistically burned.

The moss garden, which was designed in the 1330’s by Musō Soseki, a Zen monk, renowned gardener, and head priest of the temple. He considered gardening a form of meditation and Kokedera is considered his masterpiece. What this garden had in abundance was dappled light: sunlight flickered in the interstices between the overhanging leaves. Over the centuries the caretakers had kept a close eye on each tree branch, rigging up a system of support whenever the weight of gravity threatened to break a branch.

The labor required to maintain these “natural-looking” gardens is mind-boggling. In one instance Janet and I observed a gardener picking tiny seed buds off a bush to prevent them from falling and seeding the ground! I think this type of attention to minutiae pervades Japanese culture not just aesthetically but morally and ethically. For example every cash register in Japan is equipped with a small rectangular plate which is passed to you and where you are expected to place the money you are paying with. Heaven forfend you be so crass as to hand the money directly to the cashier! It is simply not done!

After lunch we went to see the famous Ryoanji Temple rock garden where it is said you can never see all of the rocks at one time. Seeing the variety of gardens it is hard to not appreciate the ingenuity of the Japanese.

Thursday, July 6, 2017, Kyoto, Japan

Fushimi Inari-taisha, the orange gated Shinto Shrine is our first stop. Inari, which means “rice” is worshipped as the patron of busines, merchants and manufacturing. The shrine consists of thousands of orange gates stacked one after another up a mountain. (We are sure Christo must have based his Gates Project on this Shrine.)

Businesses pay to erect gates for themselves; there are set prices depending on the size of the gate. Images of foxes with a key (to the granary) in their mouth abound in the Shrine. In fact. there is a granary at the base of the Shrine that now functions as a gift shop. Sam noticed the thickness of the door (close to two feet); he asked what the building was used for and was told it was used to store the rice. Below, Lee, Sam and Janet. (Note the statue of foxes atop pillars on either side of the staircase.)

Next we visited the garden of one of the Tofuku-ji Zen Temple complex. Tofuku-ji is one of the five Kyoto Gozan temples. It was was built in the mid-13th century and has maintained its Zen architecture since the Middle Ages. This was the first sand garden we encountered. The photographs don’t convey the peaceful, contemplative quality of the open garden courtyard. Below are Lee and Janet camping it up for the camera in front of the temple building.

Wednesday, July 5, 2017, Tokyo to Kyoto, Japan.

We train to Kyoto using our Japan Rail Pass. It is a three-hour trip. Lee is tired and Sam, who is allergic to shell fish is suffering the after effects of the three gigantic raw oysters he ate at the Fish Market yesterday morning. Eventually we arrive in Kyoto and make our way to the Hotel Monterrey in the Nakagyo Ward where we settle in.

In the early evening we set out to explore the neighborhood and we are totally charmed! Our hotel is on a main generic avenue, but an eight minute stroll takes us to a walkable neighborhood full of old wooden houses, restaurants, boutiques, and shopping arcades. From our hotel we can walk to the river and canals, and to the Gion District, historically known for its geisha houses. These photographs were taken late in the evening.

We set out for a recommended eel restaurant only to find it closed on Wednesdays, so we wander up and down the canal getting hungrier and hungrier. It is close to 9:00 pm and we decide to just find a restaurant. For no reason I can think of we focus on the menu of a windowless restaurant only to find the menu written entirely in Japanese. Suddenly the door opens and a man appears in the doorway. We ask if he has an English menu and he says No, regrettably he doesn’t. He assumes we will go elsewhere and backs up to close the door. I think it was the fact that we were not getting a hard sell from him: he didn’t care whether we ate there or not. In an instant we all decide we don’t need to be able to read the menu and we pile in.

We enter a tiny room with three small tables in a row. There is a doorway to a second room out of which drift some voices. I wouldn’t call the place a hole in the wall; I would says it’s closer to a hallway. The proprietor pushes two tables together and the four of us slide in. Soon thereafter a more formally dressed younger man walks in holding a single handwritten photocopied piece of paper that is the restaurant menu. The man speaks English well; we learn he is a local English teacher. He tells us, “You have discovered my favorite restaurant!” He said, “I always eat here, because there is only him (indicating the chef), he is the only one who cooks.” It is late in the evening, we are obviously the last customers; we ask the chef to feed us whatever he wants. We leave everything up to him.

He proceeds to serve us an incredible meal starting with some slices of sashimi. The dishes we are served are small and simple — a small mixed salad, a dish of eggplant, some vegetable tempura, some tofu, a dish of chicken necks (de-boned). The dishes have the look and feel of home cooking except that they are cooked to perfection. Nothing, absolutely nothing disappoints. We bemoan that this experience has spoiled us. I said, “Now that I know what tempura is supposed to taste like I don’t think I’ll ever be able to order it again…” (For the record, tempura should be light, fluffy, and so flaky you can see the individual flakes of batter.)

The name of the restaurant is alphabetized as KAMON. My colleague, Maggie Guo, tells me it translates something akin to BBQ…

I think the meal came to about US$50, sake included.

Below I immortalize the restaurant’s business card.

Tuesday, July 4, 2017, Tokyo, Japan

We started the morning by walking to the Tsukiji Fish Market, the biggest wholesale seafood market in the world. The inner wholesale market has restricted entry, but the outer retail market attracts tourists both foreign and domestic. Let us just say we ate our fill.